The next big idea in urbanism may be right under architects’ noses, as demonstrated by a just-completed urban renewal in Istanbul.

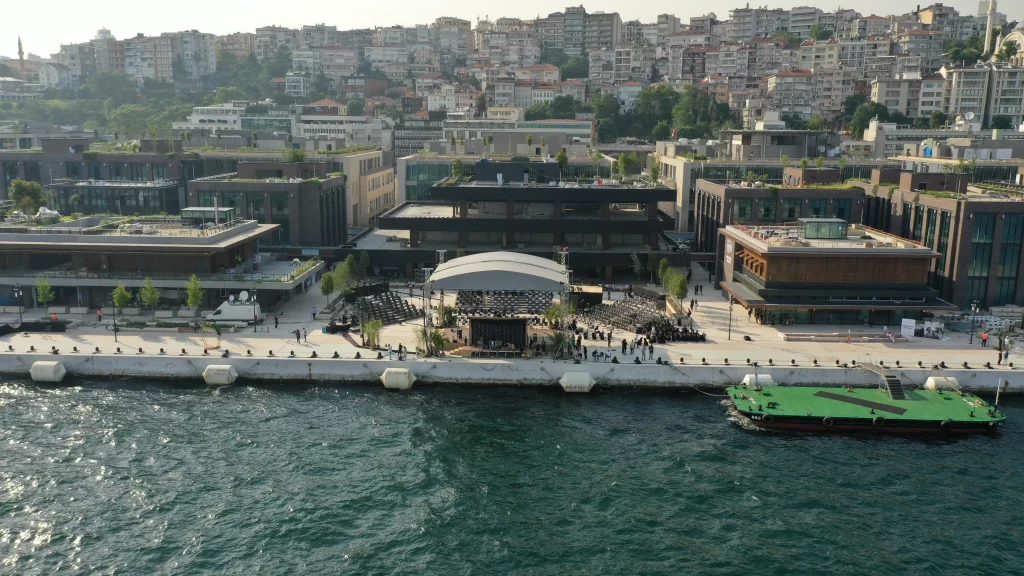

On paper, Galataport has many of the features of everyday megaprojects: 400,000 square meters of construction, 250 retail units, enough parking for 2,400 vehicles, a 177-room Peninsula hotel, a Renzo Piano–designed museum, a Salt Bae restaurant, and 1.2 kilometers of new coastline that renovated a section of town inaccessible to the public for 200 years—all bundled in a $1.7 billion price tag. On paper, it’s Turkish Canary Wharf or Hudson Yards or whatever other Pudongulous eyesore. But the reality is that Galataport has transcended megaproject design by embracing an about-face on pomp. It’s the world’s first underground cruise ship port, projecting 15,000 passengers a day and 25 million annual visitors.

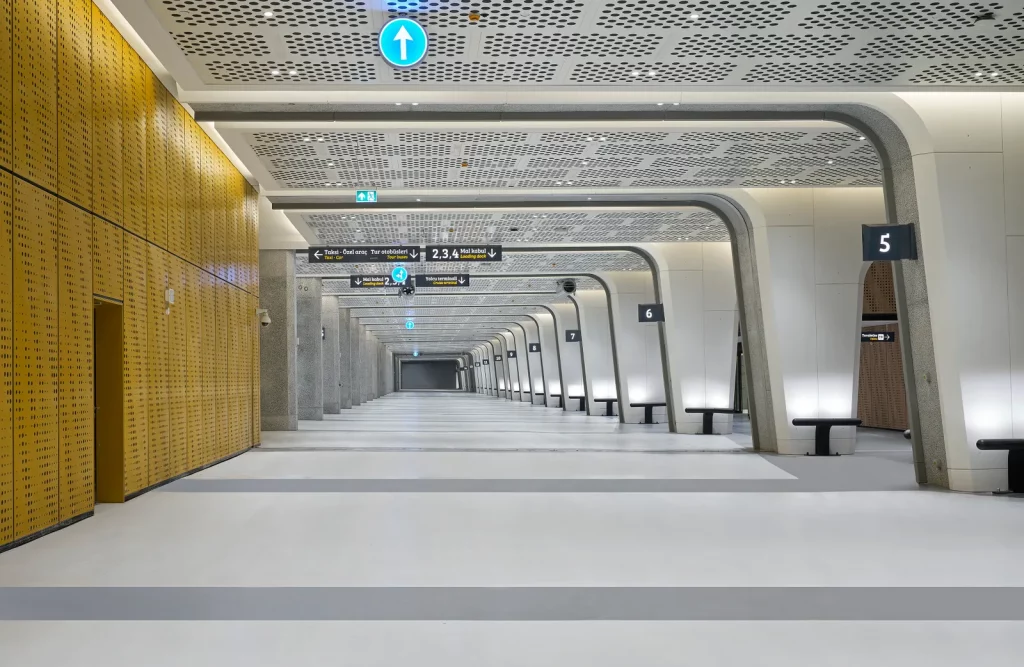

As ships dock, patches of sidewalk lift 90 degrees to reveal ramps that descend into customs and passport control (the raised sidewalks double as security barriers).

“We tried to find a system to open up the view,” said Figen Ayan, Galataport’s chief port officer. “We thought of building down like a parking lot because, really, what do you do in a terminal building? You handle luggage. You board buses. Customs. It’s not really fancy or sexy. So, do they logistically need something extravagant? No. This can be done underground.” She called the project “not just an expansion of our city, but also an expansion of our knowledge.”

There were plenty of engineering challenges, said Galataport Executive Board Member Erdem Tavas: “We didn’t build it beside the sea. We built it in the sea. It was lots of engineering innovation.” He flagged that such construction sidestepped archaeological concerns in the historic port town that was the terrestrial endpoint for the ancient Spice Road and has been the capital of two of the world’s most influential empires. “There’s no Atlantis there,” he joked.

A rendering of Galataport.

But in a city with so much history, Galataport is “a project that will last for hundreds of years,” said Ali Pusat, the assistant general manager who oversaw construction. He noted that sea level rise over the past 100 years had been 30 to 35 centimeters, but that Galataport was built to withstand three meters of sea level rise. And all buildings use seawater as a coolant, for greater sustainability.

James Ramsey, the New York–based boutique architect to the megarich through RAAD Studio, recently took a tour of Galataport, drawn by the interest he developed for underground ventures during his proposed Lowline, the world’s first underground park.

Inside the new underground cruise ship terminal.

“In submerging the edifice they’ve subverted the paradigm. It’s a clever, practical consideration that is respectful of the urban fabric,” he said. “Every infrastructure project I’ve ever seen like this is a monumental gateway. That kind of monumentalism is something embraced once upon a time—definitely with midcentury modernism or early 20th-century modernism—but approaching it from a broader viewpoint or context makes for a more sensitive urban intervention. Galataport is an evolved level of urbanism. People should open their eyes to a broader range of thinking about what’s possible in doing things that are traditionally only ever done in one fashion.”

Galataport, flanked by one of Istanbul’s landmark mosques.

He continued: “What are your priorities when you develop something like that in a place like that? The edifice or the city? They took this tear in the urban fabric and knitted it back together: continuing the axes of the city, being sensitive to the height of buildings and human-scale rhythm of design. You can have your pride take a back seat to the sensitivity of how you’re treating the city. Istanbul itself is the jewel here, a palimpsest of millennia. It’s the star, not whatever glass thing dreamt up by a starchitect. Galataport doesn’t have some individual landmark or hub. It’s an egoless design.”

In the Lowline’s heyday, Ramsey was approached to pursue similar projects in London, Moscow, Paris, and Seoul. He said major port cities like Miami, Rotterdam, Shanghai, and Singapore would do well to consider Galataport’s example.

Galataport didn’t just renovate its old post office building into a “fashion galleria:” it painstakingly restored each individual slate tile on the roof — all 25,000 of them. Another Galataport surprise is a fully restored 1848 clock tower that had been buried for decades. Its centrality in a plaza is Galataport’s boldest design strategy: that if ports can be submerged, so can 21st-century vanity. If you must know, the master plan was designed by Dror + Gensler; the façade designers and creative consultants were Tanju Özelgin and Arif Özden of TO Studio, BEA Architects developed the underground cruise terminal design and transportation circulation plans, the cruise terminal’s interior was designed by Autoban, and the architect of record was Norm Architecture.